Understanding Distortion & Trapped Air When Firing Bullseye Glass

Two common problems encountered when fusing glass are distortions of shape and unanticipated bubbles. To avoid these effects—or to engineer them into your work—you need to learn how to control volume and trapped air during firing.

Understanding Volume

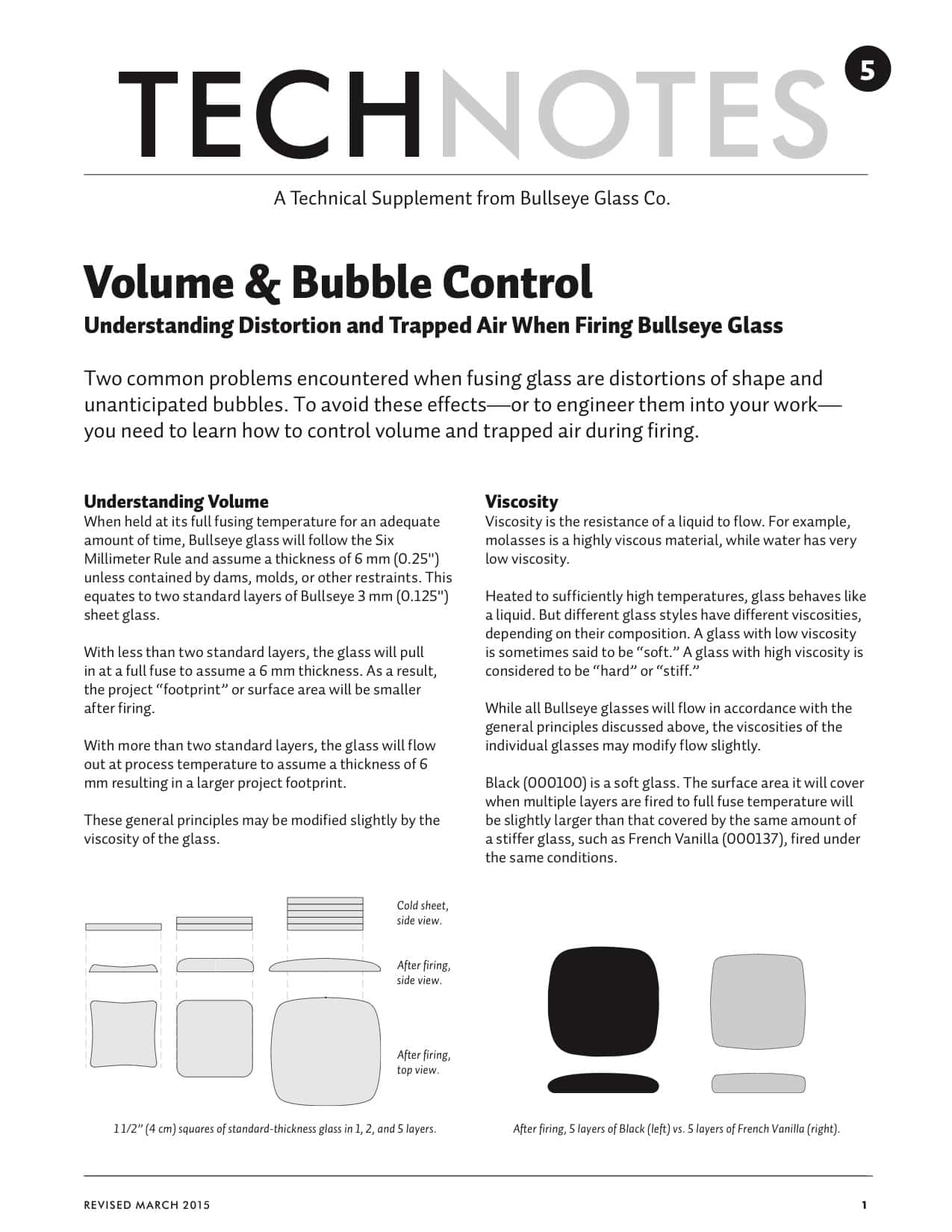

When held at its full fusing temperature for an adequate amount of time, Bullseye glass will follow the Six Millimeter Rule and assume a thickness of 6 mm (0.25˝) unless contained by dams, molds, or other restraints. This equates to two standard layers of Bullseye 3 mm (0.125˝) sheet glass.

With less than two standard layers, the glass will pull in at a full fuse to assume a 6 mm thickness. As a result, the project “footprint” or surface area will be smaller after firing.

With more than two standard layers, the glass will flow out at process temperature to assume a thickness of 6 mm resulting in a larger project footprint.

These general principles may be modified slightly by the viscosity of the glass.

Viscosity

Viscosity is the resistance of a liquid to flow. For example, molasses is a highly viscous material, while water has very low viscosity.

Heated to sufficiently high temperatures, glass behaves like a liquid. But different glass styles have different viscosities, depending on their composition. A glass with low viscosity is sometimes said to be “soft.” A glass with high viscosity is considered to be “hard” or “stiff.”

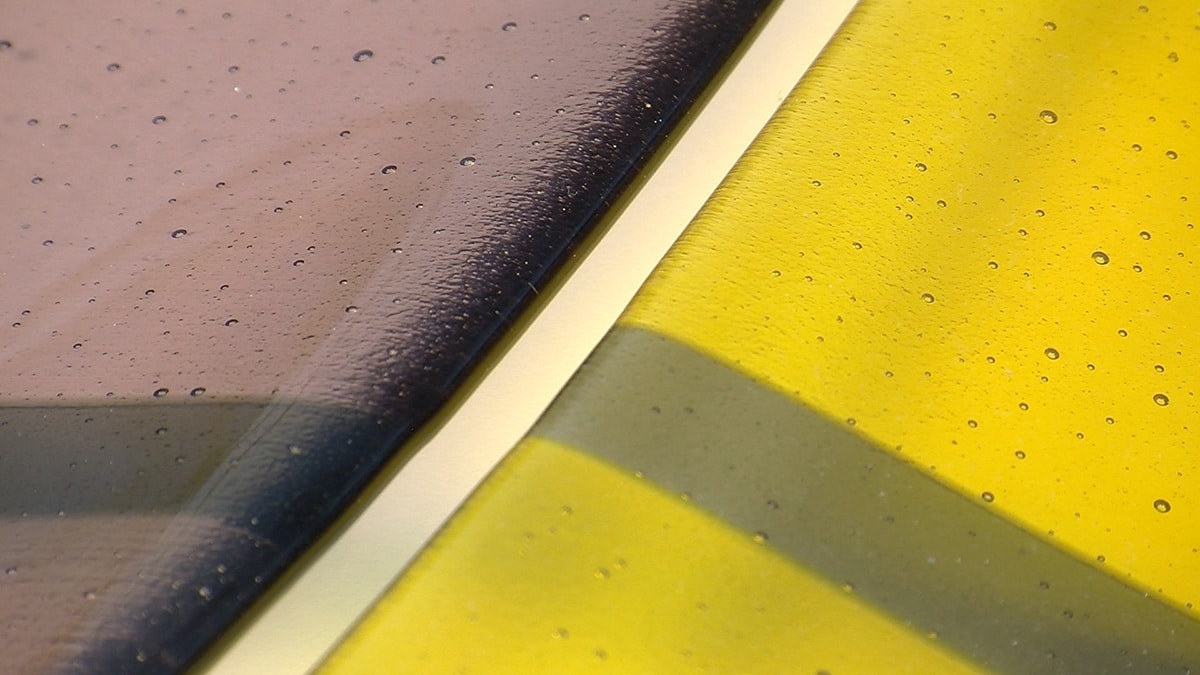

While all Bullseye glasses will flow in accordance with the general principles discussed above, the viscosities of the individual glasses may modify flow slightly.

Black (000100) is a soft glass. The surface area it will cover when multiple layers are fired to full fuse temperature will be slightly larger than that covered by the same amount of a stiffer glass, such as French Vanilla (000137), fired under the same conditions.